- Home

Page 2

Page 2

Jamaica Inn

Jamaica Inn The House on the Strand

The House on the Strand I'll Never Be Young Again

I'll Never Be Young Again Rebecca

Rebecca The Scapegoat

The Scapegoat The Birds and Other Stories

The Birds and Other Stories My Cousin Rachel

My Cousin Rachel Don't Look Now

Don't Look Now Mary Anne

Mary Anne Hungry Hill

Hungry Hill Don't Look Now and Other Stories

Don't Look Now and Other Stories The Loving Spirit

The Loving Spirit Rule Britannia

Rule Britannia The King's General

The King's General The Breaking Point: Short Stories

The Breaking Point: Short Stories The Flight of the Falcon

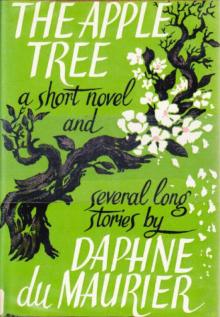

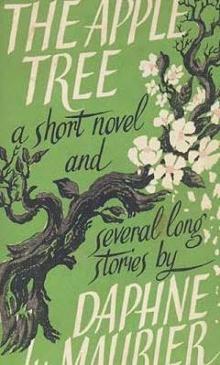

The Flight of the Falcon The Apple Tree: a short novel & several long stories

The Apple Tree: a short novel & several long stories The Breaking Point

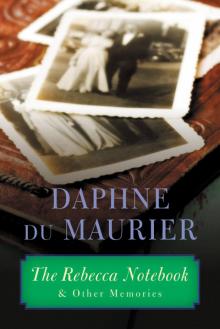

The Breaking Point The Rebecca Notebook

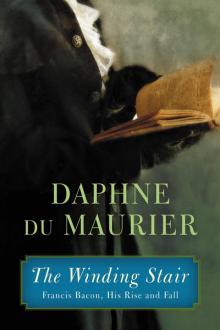

The Rebecca Notebook The Winding Stair: Francis Bacon, His Rise and Fall

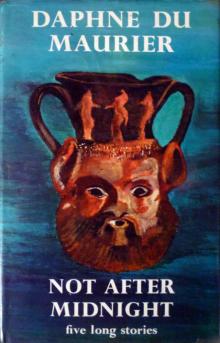

The Winding Stair: Francis Bacon, His Rise and Fall Not After Midnight & Other Stories

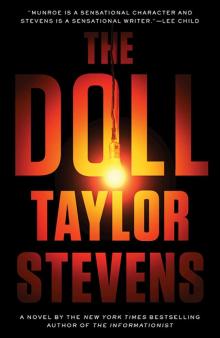

Not After Midnight & Other Stories The Doll

The Doll The Apple Tree

The Apple Tree