- Home

- Daphne Du Maurier

The Birds and Other Stories Page 14

The Birds and Other Stories Read online

Page 14

It was mercifully swift, the illness that took her from him. Influenza, followed by pneumonia, and she was dead within a week. He hardly knew how it happened, except that as usual she was overtired and caught a cold, and would not stay in bed. One evening, coming home by the late train from London, having sneaked into a cinema during the afternoon, finding release among the crowd of warm friendly people enjoying themselves--for it was a bitter December day--he found her bent over the furnace in the cellar, poking and thrusting at the lumps of coke.

She looked up at him, white with fatigue, her face drawn.

"Why, Midge, what on earth are you doing?" he said.

"It's the furnace," she said, "we've had trouble with it all day, it won't stay alight. We shall have to get the men to see it tomorrow. I really cannot manage this sort of thing myself."

There was a streak of coal dust on her cheek. She let the stubby poker fall on the cellar floor. She began to cough, and as she did so winced with pain.

"You ought to be in bed," he said, "I never heard of such nonsense. What the dickens does it matter about the furnace?"

"I thought you would be home early," she said, "and then you might have known how to deal with it. It's been bitter all day, I can't think what you found to do with yourself in London."

She climbed the cellar stairs slowly, her back bent, and when she reached the top she stood shivering and half closed her eyes.

"If you don't mind terribly," she said, "I'll get your supper right away, to have it done with. I don't want anything myself."

"To hell with my supper," he said, "I can forage for myself. You go up to bed. I'll bring you a hot drink."

"I tell you, I don't want anything," she said. "I can fill my hot-water bottle myself. I only ask one thing of you. And that is to remember to turn out the lights everywhere, before you come up." She turned into the hall, her shoulders sagging.

"Surely a glass of hot milk?" he began uncertainly, starting to take off his overcoat; and as he did so the torn half of the ten-and-sixpenny seat at the cinema fell from his pocket onto the floor. She saw it. She said nothing. She coughed again and began to drag herself upstairs.

The next morning her temperature was a hundred and three. The doctor came and said she had pneumonia. She asked if she might go to a private ward in the cottage hospital, because having a nurse in the house would make too much work. This was on the Tuesday morning. She went there right away, and they told him on the Friday evening that she was not likely to live through the night. He stood inside the room, after they told him, looking down at her in the high impersonal hospital bed, and his heart was wrung with pity, because surely they had given her too many pillows, she was propped too high, there could be no rest for her that way. He had brought some flowers, but there seemed no purpose now in giving them to the nurse to arrange, because Midge was too ill to look at them. In a sort of delicacy he put them on a table beside the screen, when the nurse was bending down to her.

"Is there anything she needs?" he said. "I mean, I can easily..." He did not finish the sentence, he left it in the air, hoping the nurse would understand his intention, that he was ready to go off in the car, drive somewhere, fetch what was required.

The nurse shook her head. "We will telephone you," she said, "if there is any change."

What possible change could there be, he wondered, as he found himself outside the hospital? The white pinched face upon the pillows would not alter now, it belonged to no one.

Midge died in the early hours of Saturday morning.

He was not a religious man, he had no profound belief in immortality, but when the funeral was over, and Midge was buried, it distressed him to think of her poor lonely body lying in that brand-new coffin with the brass handles: it seemed such a churlish thing to permit. Death should be different. It should be like bidding farewell to someone at a station before a long journey, but without the strain. There was something of indecency in this haste to bury underground the thing that but for ill-chance would be a living breathing person. In his distress he fancied he could hear Midge saying with a sigh, "Oh, well..." as they lowered the coffin into the open grave.

He hoped with fervor that after all there might be a future in some unseen Paradise and that poor Midge, unaware of what they were doing to her mortal remains, walked somewhere in green fields. But who with, he wondered? Her parents had died in India many years ago; she would not have much in common with them now if they met her at the gates of Heaven. He had a sudden picture of her waiting her turn in a queue, rather far back, as was always her fate in queues, with that large shopping bag of woven straw which she took everywhere, and on her face that patient martyred look. As she passed through the turnstile into Paradise she looked at him, reproachfully.

These pictures, of the coffin and the queue, remained with him for about a week, fading a little day by day. Then he forgot her. Freedom was his, and the sunny empty house, the bright crisp winter. The routine he followed belonged to him alone. He never thought of Midge until the morning he looked out upon the apple tree.

Later that day he was taking a stroll round the garden, and he found himself drawn to the tree through curiosity. It had been stupid fancy after all. There was nothing singular about it. An apple tree like any other apple tree. He remembered then that it had always been a poorer tree than its fellows, was in fact more than half dead, and at one time there had been talk of chopping it down, but the talk came to nothing. Well, it would be something for him to do over the weekend. Axing a tree was healthy exercise, and applewood smelled good. It would be a treat to have it burning on the fire.

Unfortunately wet weather set in for nearly a week after that day, and he was unable to accomplish the task he had set himself. No sense in pottering out of doors this weather, and getting a chill into the bargain. He still noticed the tree from his bedroom window. It began to irritate him, humped there, straggling and thin, under the rain. The weather was not cold, and the rain that fell upon the garden was soft and gentle. None of the other trees wore this aspect of dejection. There was one young tree--only planted a few years back, he recalled quite well--growing to the right of the old one and standing straight and firm, the lithe young branches lifted to the sky, positively looking as if it enjoyed the rain. He peered through the window at it, and smiled. Now why the devil should he suddenly remember that incident, years back, during the war, with the girl who came to work on the land for a few months at the neighboring farm? He did not suppose he had thought of her in months. Besides, there was nothing to it. At weekends he had helped them at the farm himself--war work of a sort--and she was always there, cheerful and pretty and smiling; she had dark curling hair, crisp and boyish, and skin like a very young apple.

He looked forward to seeing her, Saturdays and Sundays; it was an antidote to the inevitable news bulletins put on throughout the day by Midge, and to ceaseless war talk. He liked looking at the child--she was scarcely more than that, nineteen or so--in her slim breeches and gay shirts; and when she smiled it was as though she embraced the world.

He never knew how it happened, and it was such a little thing; but one afternoon he was in the shed doing something to the tractor, bending over the engine, and she was beside him, close to his shoulder, and they were laughing together; and he turned round, to take a bit of waste to clean a plug, and suddenly she was in his arms and he was kissing her. It was a happy thing, spontaneous and free, and the girl so warm and jolly, with her fresh young mouth. Then they went on with the work of the tractor, but united now, in a kind of intimacy that brought gaiety to them both, and peace as well. When it was time for the girl to go and feed the pigs he followed her from the shed, his hand on her shoulder, a careless gesture that meant nothing really, a half caress; and as they came out into the yard he saw Midge standing there, staring at them.

"I've got to go in to a Red Cross meeting," she said. "I can't get the car to start. I called you. You didn't seem to hear."

Her face was frozen. Sh

e was looking at the girl. At once guilt covered him. The girl said good evening cheerfully to Midge, and crossed the yard to the pigs.

He went with Midge to the car and managed to start it with the handle. Midge thanked him, her voice without expression. He found himself unable to meet her eyes. This, then, was adultery. This was sin. This was the second page in a Sunday newspaper--"Husband Intimate with Land Girl in Shed. Wife Witnesses Act." His hands were shaking when he got back to the house and he had to pour himself a drink. Nothing was ever said. Midge never mentioned the matter. Some craven instinct kept him from the farm the next weekend, and then he heard that the girl's mother had been taken ill and she had been called back home.

He never saw her again. Why, he wondered, should he remember her suddenly, on such a day, watching the rain falling on the apple trees? He must certainly make a point of cutting down the old dead tree, if only for the sake of bringing more sunshine to the little sturdy one; it hadn't a fair chance, growing there so close to the other.

On Friday afternoon he went round to the vegetable garden to find Willis, the jobbing gardener, who came three days a week, to pay him his wages. He wanted, too, to look in the toolshed and see if the axe and saw were in good condition. Willis kept everything neat and tidy there--this was Midge's training--and the axe and saw were hanging in their accustomed place upon the wall.

He paid Willis his money, and was turning away when the man suddenly said to him, "Funny thing, sir, isn't it, about the old apple tree?"

The remark was so unexpected that it came as a shock. He felt himself change color.

"Apple tree? What apple tree?" he said.

"Why, the one at the far end, near the terrace," answered Willis. "Been barren as long as I've worked here, and that's some years now. Never an apple from her, nor as much as a sprig of blossom. We were going to chop her up that cold winter, if you remember, and we never did. Well, she's taken on a new lease now. Haven't you noticed?" The gardener watched him smiling, a knowing look in his eye.

What did the fellow mean? It was not possible that he had been struck also by that fantastic freak resemblance--no, it was out of the question, indecent, blasphemous; besides, he had put it out of his own mind now, he had not thought of it again.

"I've noticed nothing," he said, on the defensive.

Willis laughed. "Come round to the terrace, sir," he said, "I'll show you."

They went together to the sloping lawn, and when they came to the apple tree Willis put his hand up and pulled down a branch within reach. It creaked a little as he did so, as though stiff and unyielding, and Willis brushed away some of the dry lichen and revealed the spiky twigs. "Look there, sir," he said, "she's growing buds. Look at them, feel them for yourself. There's life here yet, and plenty of it. Never known such a thing before. See this branch too." He released the first, and leaned up to reach another.

Willis was right. There were buds in plenty, but so small and brown that it seemed to him they scarcely deserved the name, they were more like blemishes upon the twig, dusty and dry. He put his hands in his pockets. He felt a queer distaste to touch them.

"I don't think they'll amount to much," he said.

"I don't know, sir," said Willis, "I've got hopes. She's stood the winter, and if we get no more bad frosts there's no knowing what we'll see. It would be some joke to watch the old tree blossom. She'll bear fruit yet." He patted the trunk with his open hand, in a gesture at once familiar and affectionate.

The owner of the apple tree turned away. For some reason he felt irritated with Willis. Anyone would think the damned tree lived. And now his plan to axe the tree, over the weekend, would come to nothing.

"It's taking the light from the young tree," he said. "Surely it would be more to the point if we did away with this one, and gave the little one more room?"

He moved across to the young tree and touched a limb. No lichen here. The branches smooth. Buds upon every twig, curling tight. He let go the branch and it sprang away from him, resilient.

"Do away with her, sir," said Willis, "while there's still life in her? Oh no, sir, I wouldn't do that. She's doing no harm to the young tree. I'd give the old tree one more chance. If she doesn't bear fruit, we'll have her down next winter."

"All right, Willis," he said, and walked swiftly away. Somehow he did not want to discuss the matter anymore.

That night, when he went to bed, he opened the window wide as usual and drew back the curtains; he could not bear to wake up in the morning and find the room close. It was full moon, and the light shone down upon the terrace and the lawn above it, ghostly pale and still. No wind blew. A hush upon the place. He leaned out, loving the silence. The moon shone full upon the little apple tree, the young one. There was a radiance about it in this light that gave it a fairy-tale quality. Small and lithe and slim, the young tree might have been a dancer, her arms upheld, poised ready on her toes for flight. Such a careless, happy grace about it. Brave young tree. Away to the left stood the other one, half of it in shadow still. Even the moonlight could not give it beauty. What in heaven's name was the matter with the thing that it had to stand there, humped and stooping, instead of looking upwards to the light? It marred the still quiet night, it spoiled the setting. He had been a fool to give way to Willis and agree to spare the tree. Those ridiculous buds would never blossom, and even if they did...

His thoughts wandered, and for the second time that week he found himself remembering the land girl and her joyous smile. He wondered what had happened to her. Married probably, with a young family. Made some chap happy, no doubt. Oh, well... He smiled. Was he going to make use of that expression now? Poor Midge! Then he caught his breath and stood quite still, his hand upon the curtain. The apple tree, the one on the left, was no longer in shadow. The moon shone upon the withered branches, and they looked like skeleton's arms raised in supplication. Frozen arms, stiff and numb with pain. There was no wind, and the other trees were motionless; but there, in those topmost branches, something shivered and stirred, a breeze that came from nowhere and died away again. Suddenly a branch fell from the apple tree to the ground below. It was the near branch, with the small dark buds upon it, which he would not touch. No rustle, no breath of movement came from the other trees. He went on staring at the branch as it lay there on the grass, under the moon. It stretched across the shadow of the young tree close to it, pointing as though in accusation.

For the first time in his life that he could remember he drew the curtains over the window to shut out the light of the moon.

Willis was supposed to keep to the vegetable garden. He had never shown his face much round the front when Midge was alive. That was because Midge attended to the flowers. She even used to mow the grass, pushing the wretched machine up and down the slope, her back bent low over the handles.

It had been one of the tasks she set herself, like keeping the bedrooms swept and polished. Now Midge was no longer there to attend to the front garden and to tell him where he should work, Willis was always coming through to the front. The gardener liked the change. It made him feel responsible.

"I can't understand how that branch came to fall, sir," he said on the Monday.

"What branch?"

"Why, the branch on the apple tree. The one we were looking at before I left."

"It was rotten, I suppose. I told you the tree was dead."

"Nothing rotten about it, sir. Why, look at it. Broke clean off."

Once again the owner was obliged to follow his man up the slope above the terrace. Willis picked up the branch. The lichen upon it was wet, bedraggled-looking, like matted hair.

"You didn't come again to test the branch, over the weekend, and loosen it in some fashion, did you, sir?" asked the gardener.

"I most certainly did not," replied the owner, irritated. "As a matter of fact I heard the branch fall, during the night. I was opening the bedroom window at the time."

"Funny. It was a still night too."

"These things often

happen to old trees. Why you bother about this one I can't imagine. Anyone would think..."

He broke off; he did not know how to finish the sentence.

"Anyone would think that the tree was valuable," he said.

The gardener shook his head. "It's not the value," he said. "I don't reckon for a moment that this tree is worth any money at all. It's just that after all this time, when we thought her dead, she's alive and kicking, as you might say. Freak of nature, I call it. We'll hope no other branches fall before she blossoms."

Later, when the owner set off for his afternoon walk, he saw the man cutting away the grass below the tree and placing new wire around the base of the trunk. It was quite ridiculous. He did not pay the fellow a fat wage to tinker about with a half-dead tree. He ought to be in the kitchen garden, growing vegetables. It was too much effort, though, to argue with him.

He returned home about half past five. Tea was a discarded meal since Midge had died, and he was looking forward to his armchair by the fire, his pipe, his whiskey and soda, and silence.

The fire had not long been lit and the chimney was smoking. There was a queer, rather sickly smell about the living room. He threw open the windows and went upstairs to change his heavy shoes. When he came down again the smoke still clung about the room and the smell was as strong as ever. Impossible to name it. Sweetish, strange. He called to the woman out in the kitchen.

"There's a funny smell in the house," he said. "What is it?"

The woman came out into the hall from the back.

"What sort of a smell, sir?" she said, on the defensive.

"It's in the living room," he said. "The room was full of smoke just now. Have you been burning something?"

Her face cleared. "It must be the logs," she said. "Willis cut them up specially, sir, he said you would like them."

"What logs are those?"

"He said it was applewood, sir, from a branch he had sawed up. Applewood burns well, I've always heard. Some people fancy it very much. I don't notice any smell myself, but I've got a slight cold."

Jamaica Inn

Jamaica Inn The House on the Strand

The House on the Strand I'll Never Be Young Again

I'll Never Be Young Again Rebecca

Rebecca The Scapegoat

The Scapegoat The Birds and Other Stories

The Birds and Other Stories My Cousin Rachel

My Cousin Rachel Don't Look Now

Don't Look Now Mary Anne

Mary Anne Hungry Hill

Hungry Hill Don't Look Now and Other Stories

Don't Look Now and Other Stories The Loving Spirit

The Loving Spirit Rule Britannia

Rule Britannia The King's General

The King's General The Breaking Point: Short Stories

The Breaking Point: Short Stories The Flight of the Falcon

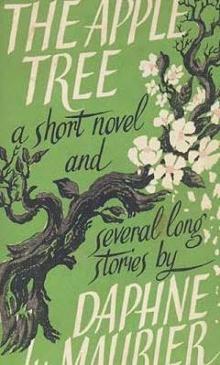

The Flight of the Falcon The Apple Tree: a short novel & several long stories

The Apple Tree: a short novel & several long stories The Breaking Point

The Breaking Point The Rebecca Notebook

The Rebecca Notebook The Winding Stair: Francis Bacon, His Rise and Fall

The Winding Stair: Francis Bacon, His Rise and Fall Not After Midnight & Other Stories

Not After Midnight & Other Stories The Doll

The Doll The Apple Tree

The Apple Tree